In my experience, most guitar players know just enough notes — by name — on the guitar to position their barre chords and scale patterns. That this deficit doesn’t hinder their ability to play good music, even great music, says more about the instrument than it does the players.

In my experience, most guitar players know just enough notes — by name — on the guitar to position their barre chords and scale patterns. That this deficit doesn’t hinder their ability to play good music, even great music, says more about the instrument than it does the players.

A characteristic unique to stringed instruments, and the guitar in particular, is the ability to shift the same scale patterns and chords to different locations on the fingerboard to handle various tonalities, allowing us to (as I like to put it) “take a minimum amount of skill and do a maximum amount of damage”.

The problem is that the guitar is not a particularly easy instrument when it comes to visualizing the fingerboard and the specific locations of notes.

Unlike a piano (where the keys are laid out in an ergonomically designed, linear, ascending order, where there is only one key to hit for any particular note, and all the sharps and flats are easy to locate and identify by name), instead the guitar is a complex combination of strings and frets presenting a confounding matrix of notes and duplicates of notes, none of which being at all intuitive to visually isolate and identify.

Early on, I struggled with memorizing the names of all the notes on every string. I’d take one string, and plot in my head every note as I ascended the fingerboard. Then I’d move on to the next string and do it all again. It didn’t take long to overload my brain with six different note maps, trying to keep them straight.

Then one day it came to me that I was going about it all wrong. Instead of memorizing the locations of 72 individual notes distributed among 6 strings (and that’s just the lower 12 frets of the guitar), I could instead memorize a couple of basic concepts, and as a result quickly name any note on the fingerboard within two seconds!

Here’s how:

Video Transcript:

This complex grid of six strings and a whole bunch of frets we call “a guitar”, at a very fundamental level, is a vast mystery… one which, in many ways, will remain a mystery for the entire life of every guitarist. It could be said this is a good thing, for as long as there are secrets to unravel, we will never run out of opportunities to learn new things and elevate our playing.

Every beginning guitarist, and the majority of intermediate players, and even many of the most stellar performers on our instrument share a common characteristic — they either have never learned, or have a difficult time remembering, the names of the notes they play on the guitar. Perhaps they know the notes on certain strings well enough to position their barre chords and scale patterns, but an ability to quickly identify, by name, any note, on every string, eludes them.

We will tackle this problem with a combination of three basic concepts that won’t take too long to memorize, but which (when combined) will make identifying any note on the guitar, within two seconds or less, easy as pie.

The three concepts are:

- A quick review of the 12-tone system

- Bass notes on the 5th and 6th strings

- Octave patterns on the guitar neck

A Quick Review of the 12-tone System

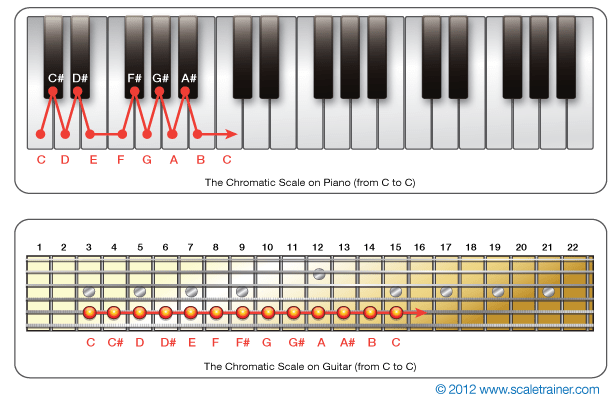

For beginning players (or those who simply need a reminder), let’s briefly review the notes of the chromatic scale: every note available to us on our instrument. The most fundamental tonal relationship in music is the octave, the reasons for which have to do with mathematical aspects of sound wave frequency which we won’t go into at present. Suffice to say:

The vast majority of all the music in the world is made using a 12-tone system. We can start on any note we want, then ascend in pitch from that note through every available note on our instrument, until we come again to the note of the same name one octave higher… and we will have gone through 12 notes in half-step increments, each equal in frequency difference from its neighbor.

Check out this handy graphic I found depicting the chromatic scale as it appears on both piano and guitar:

You will see that we have seven “natural” note names (A B C D E F G), and that in between most of these we have what’s called “accidentals” or “chromatics” (sharp and flat versions of the neighboring notes). This recurring pattern is probably best visualized on the piano, where the pattern of white and black keys make this structure more obvious than on a guitar.

Two things to remember about all this:

- Between most adjacent natural notes, there is a note which is the sharp (raised pitch) of the lower note, or the flat (lowered pitch) of the higher note. Thus most adjacent natural notes are a whole-step apart (BTW, which of these names we typically use — flat (b) or sharp (#) — is mostly determined by the particular key in which we’re playing).

- The two lone exceptions to the above rule are the natural note-sets B-C, and E-F. These are the two spots (on the piano) where there is no black key (accidental) between them. And as you learn the notes on your guitar, the same holds true. This stuff is pure music theory, and applies to any instrument you want to play.

So the chromatic scale (every note we have on the instrument we’re playing, whatever it is), starting from A, reads like this:

A – A#/Bb – B – C – C#/Db – D – D#/Eb – E – F – F#/Gb – G – G#/Ab –>

Beginning from any other note simply rolls the note order around itself in similar fashion.

![]()

Bass Notes on the 5th and 6th Strings

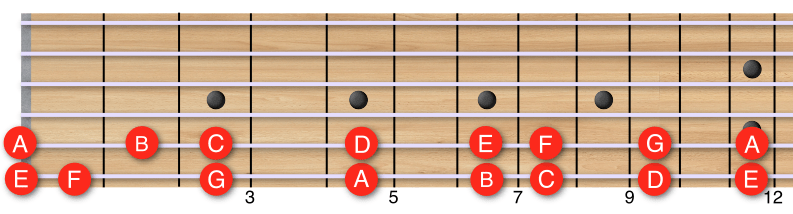

Knowing the natural notes on the 5th and 6th strings is of fundamental importance for any guitarist. In a practical sense, we need to know these notes to be able to position our barre chords and scale patterns on the neck so we can play in the correct key for the tune at-hand. Here’s a chart of the natural notes on the two bass strings:

In standard tuning, the open 6th string is E, and the open 5th string is A. Proceeding up either string (keeping in mind the construction of the chromatic scale we just covered), we can establish where the natural notes lie on the neck.

- Note that, with the exception of the first two frets, all the natural notes lay side by side (G & C at the 3rd fret, A & D at the 5th fret, etc) all the way to the 12th fret. Above the 12th fret, simply apply the same layout as we did in the lower part of the fretboard.

- The accidentals (sharps and flats) will obviously occur between the natural notes on each string. They were omitted on the chart for the sake of simplicity and clarity. If you know your natural notes, the accidentals are easy to find.

![]()

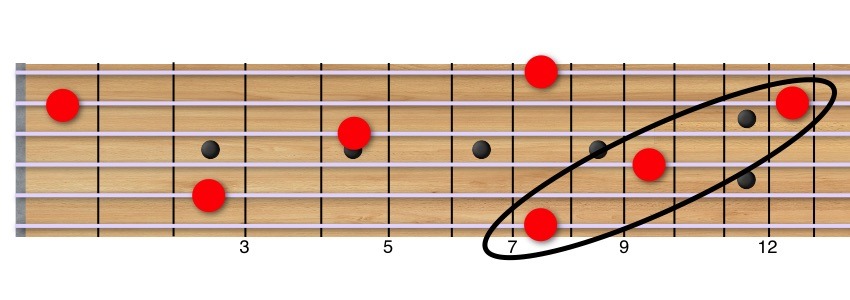

Octave Patterns On The Guitar Neck

The location of all our octave notes is a handy thing to know. Being able to see all the octaves on the neck helps us in playing scales and chords, shifting key center, identifying intervals, etc. Very fundamental stuff if you want to master the fingerboard.

And the good news is, there are actually relatively few octaves to keep track of, and with a few easy-to-remember rules, developing a mental grid of them is fairly easy.

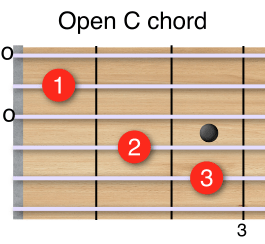

Let’s start with a basic C chord, one of the first open chords we all learn.

The notes played by the 1st and 3rd fingers are both C. Remember the relationship between those two notes on the neck (from C on the 5th string, go 3 strings over, 2 frets down… or vice versa).

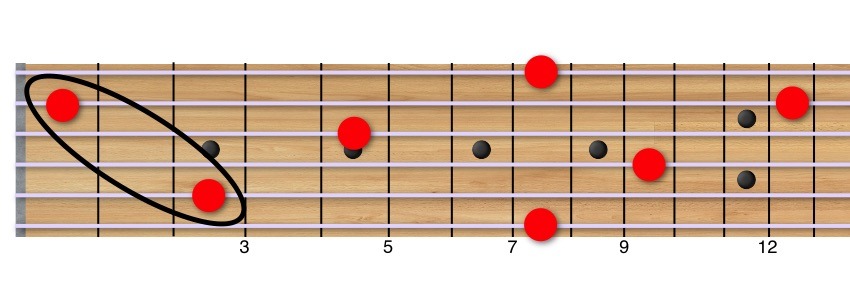

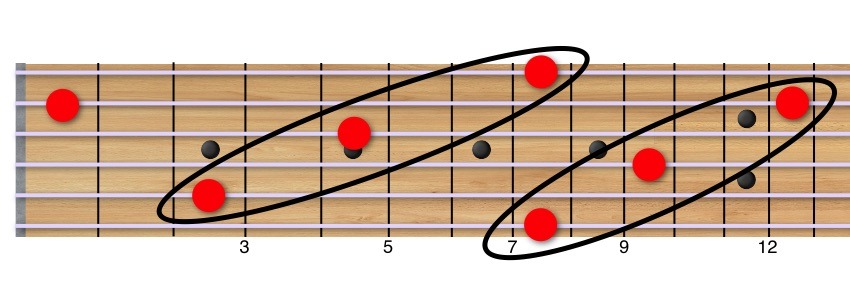

Now here’s a graphic of all the octaves on the neck, oriented around the note C.

Remember that the spacial relationships between the notes never changes,

but simply rolls around the neck, centered on the particular note we’re identifying!

We’ll go over the rules of how to navigate the patterns one by one.

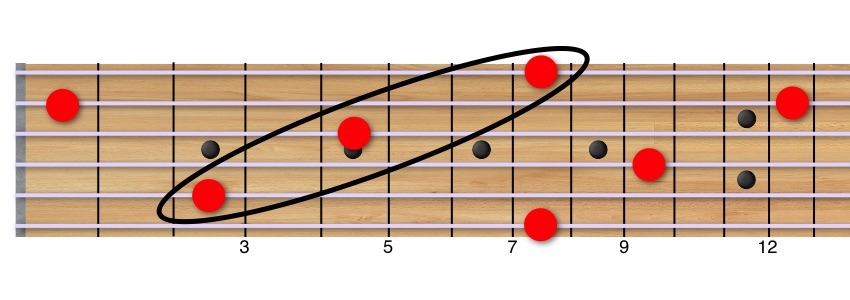

From that note, go 2 strings over and 3 frets up.

This gives you octaves from the 5th string, to the 3rd, and all the way to the 1st string.

Remember: “2 and 2, then 2 and 3”.

Sidebar: The reason for the difference in the diagonal arrangement of octaves (“2 and 2, then 2 and 3”) is due to the deviation in tuning between the 2nd and 3rd strings, which is a half-step less than the tuning between all the other strings. Sounds arbitrary, yeah… but it’s this one little deviance in the tuning of the guitar that makes the instrument so accessible, easy to play, and navigate.

Took me years to figure that out!

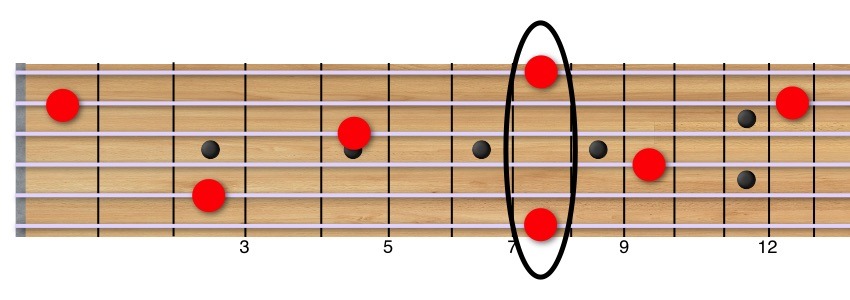

the name of the note we have on the 1st is also the name of the note we have on the 6th.

2 strings over, 2 frets up, followed by 2 strings over, 3 frets up.

This takes you all the way to the 2nd string, 13th fret.

And guess what… you’ve gone up an entire octave on the neck from the C down there on the 2nd string, 1st fret.

From here on, the grid simply rolls around again, repeating itself on up the neck.

And there you have it! Just a few little bits to memorize, and suddenly you find the fretboard opening up to you in glorious ways. What can you do with this knowledge, you ask?

- You can take any bass note you know by name on the 5th or 6th strings, and quickly extrapolate every octave of that note, anywhere on the neck.

- Conversely, you can be playing some unknown note up high in the strings somewhere, and quickly trace it back down to one of the bass notes you’ve memorized on the bottom two strings, thus establishing its identity.

Conclusion

Imagine you have a hundred friends, people you see every day, and care about deeply… but you don’t know any of their names. It would make remembering them, organizing them in your head, identifying relationships that exist (or could possibly exist) between them… even thinking about them in meaningful ways… a mite difficult, wouldn’t it?

And yet guitar and other stringed instrument players do this every day in the context of making their music. We rip through riffs and licks and all the other ways of the hand without actually knowing what notes we play!

Now, some players argue that the names of notes don’t matter all that much, that it’s all about intervallic relationships and well-worn patterns of play. And there’s some truth to that… not being able to identify the name of every note we play certainly doesn’t mean our music suffers for that lack of awareness.

Call me fussy… but I like being able to say hello to a note by its proper name, to treat it as well as I would any of my good friends, and in the day-to-day process of making my music, see how well that note plays with all the other notes, which I also know by name.

As with human relationships, all this takes a little effort. But it just seems to me the respectful way to be with all these precious bits of sound that play such an important role in our lives and music.

© 2018 Jeff Foster. All Rights Reserved.

![]()